For Tammara, our dear friend whose precious life was tragically taken on October 17, 2020.

Ten years ago, my twin, stepsister, friends and I made this work together. Given the majority of our friends and family members became mothers much younger than what is considered ‘normal’, we originally sought to share the intimate lived experiences of young motherhood. My twin sister had a baby at nineteen, my stepsister had five babies by twenty-four, and like many of our friends and extended family, I also had several children before the age of thirty. Along with my own babies, these children are my nieces, nephews and godchildren. They have enriched our lives considerably—not ‘mistakes’ as deficit discourse around young motherhood might have us believe.

Just as our families have grown, so has our project—with friends and extended kin from across several communities contributing. However, a lot has changed since 2011. In recent years, our lives have increasingly intersected with the carceral state—sometimes in violent and explicit ways. We soon realised that our shared stories have long been shaped by interlocking systems of structural violence, institutions, relentless bureaucratic processes, and violent histories. Yet, what remained forgotten within the administration, arbitrary decision-making, paperwork, court documents, police statements, criminal indexes and case files that recorded us were the intimate dimensions of our lives.

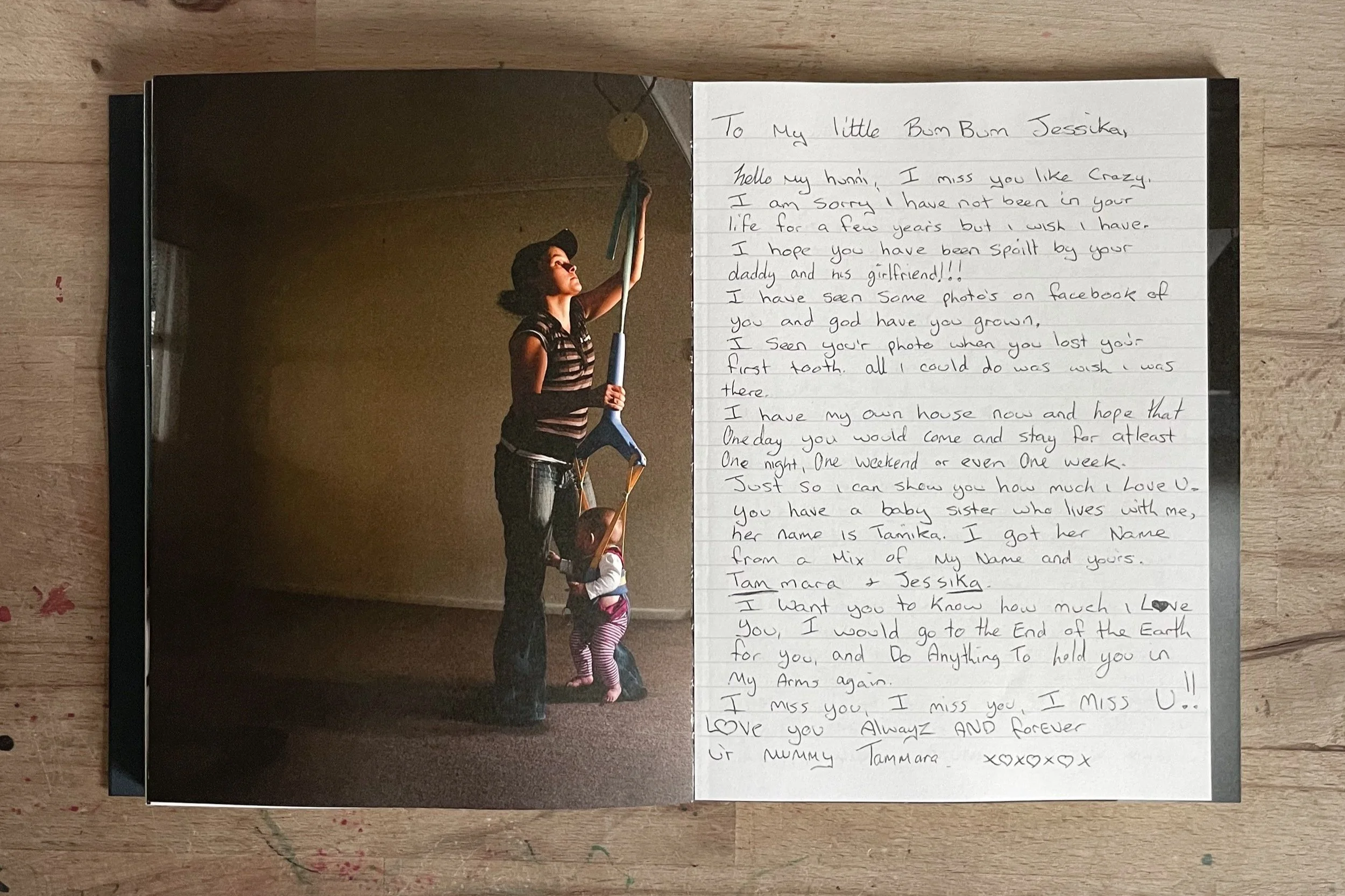

Navigating carceral bureaucracy and surveillance, we started to record our intimate relations as they extended across carceral geographies. From six-minute monitored prison phone calls to handwritten letters that circulated between us, we began to collect evidence of this time beyond the bureaucratic documents that otherwise represent this experience. Behind bars, my stepsister and friends produced personal archives, including journals, letters, family photos, state-issued documents, and criminal indexes that represented their criminality. During their incarceration, they would mail these personal archives to me to contribute to what we now consider our co-created archive.

It was during this time, while incarcerated, that Tammara would single-handedly highlight, redact, and amend the pages of errors within the criminal records and family court documents that marked her a ‘criminal’ and ‘unfit mother’. Unveiling the ineptitude of the ‘official record’, Tammara’s acts of resistance question whose voices are recorded and whose voices are silenced, whose voices are deemed credible and whose voices are not. It was Tammara who challenged me to see who we really are: whole human beings, with complex lived experiences, whose intimate lives were meant to be forgotten within the pages of paper that record us. It was her refusal to accept this authority that prompted us to consider the value of our co-created ‘counter’ archive as a site of resistance.

Tammara, I will forever cherish our friendship, our childhood memories and the past decade we shared together. Your commitment to sharing your story has been inspiring, rewarding and at times heartbreaking. I am still struggling to accept that you are gone. You taught me to care deeply. Instead of pushing our loved ones away, you taught me to bring them closer; despite our flaws, we are worthy of love. Unlike the documents that marked you, you were:

a daughter

a mother

a sister

a partner

an aunty and friend.

Finally free—

forever in our hearts—

you will never be forgotten.